Biography

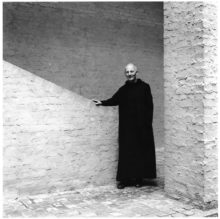

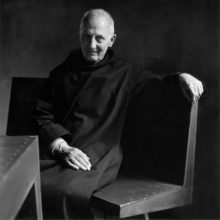

Dom Hans van der Laan, life and works

This biography is written by Brother Lambertus Moonen OSB in 2001

and edited by Hans van der Laan jr. in 2018.

Youth and education

Hans van der Laan was born in Leiden on 29 December 1904 as the ninth child of architect Leonard van der Laan (1864-1942) and Anna Stadhouder (1871-1941). His paternal grandfather (1871-1941) had been a gardener at the royal gardens in The Hague, his maternal grandfather a tailor in Leiden. In 1891 his father settled his architect’s office in Leiden. He married in 1893 and founded a family of eleven children, six boys and five girls. Of the boys, Jan, the eldest (1896-1986), Hans and the youngest, Nico (1908-1986) became also architect after studying at the ‘Technische Hogeschool’ of Delft. Hans began his study in 1923, two years after he finished his secondary school. The year 1921 he passed in a sanatorium and the year 1922 he was employed at the office of his father, who had entered shortly before a partnership with his eldest son Jan.

During those two years Hans spent much time on his growing interest in architecture by reading. For instance, H.P. Berlage’s book: ‘Schoonheid in samenleving’ (‘Beauty in society’) opened for him a world that evidently was absent in Delft. Architectural education in those days was generally confined to nineteenth-century neoclassicism and all teachers originated from before the first world-war. Henri Evers, the architect of the Rotterdam town hall, set the tone in Delft. But in 1924 M. Granpré Molière (1883-1972) was appointed to be professor for the first two years of study. In him the young student found a true master. But after a few months, in the autumn of 1925 he received teachings from professor Van der Steur, with whom he directly came in conflict. Students in their third year of study had to make their own designs, but those of Hans van der Laan were all rejected. In the same autumn he founded, together with some fellow-students, a study-group, the ‘Bouwkundige Studiekring’ BSK (‘Architectural Study Circle’), aiming to discover themselves the very basics of architecture, which they missed in regular teaching. During a year Hans guided this group, assembling at professor Granpré Molière’s house. The papers of Le Corbusier and those of ‘De Stijl’-group were discussed, as well as the just published book of Jacques Maritain: ‘Art et scholastique’. The last lecture given by Hans in the BSK was about the Domtoren in Utrecht and implied a serious trial to fully investigate the ins and outs of its measures.

Youth and education

Hans van der Laan was born in Leiden on 29 December 1904 as the ninth child of architect Leonard van der Laan (1864-1942) and Anna Stadhouder (1871-1941). His paternal grandfather (1871-1941) had been a gardener at the royal gardens in The Hague, his maternal grandfather a tailor in Leiden. In 1891 his father settled his architect’s office in Leiden. He married in 1893 and founded a family of eleven children, six boys and five girls. Of the boys, Jan, the eldest (1896-1986), Hans and the youngest, Nico (1908-1986) became also architect after studying at the ‘Technische Hogeschool’ of Delft. Hans began his study in 1923, two years after he finished his secondary school. The year 1921 he passed in a sanatorium and the year 1922 he was employed at the office of his father, who had entered shortly before a partnership with his eldest son Jan. During those two years Hans spent much time on his growing interest in architecture by reading. For instance, H.P. Berlage’s book: ‘Schoonheid in samenleving’ (‘Beauty in society’) opened for him a world that evidently was absent in Delft. Architectural education in those days was generally confined to nineteenth-century neoclassicism and all teachers originated from before the first world-war. Henri Evers, the architect of the Rotterdam town hall, set the tone in Delft. But in 1924 M. Granpre Molie re (1883-1972) was appointed to be professor for the first two years of study. In him the young student found a true master. But after a few months, in the autumn of 1925 he received teachings from professor Van der Steur, with whom he directly came in conflict. Students in their third year of study had to make their own designs, but those of Hans van der Laan were all rejected. In the same autumn he founded, together with some fellow-students, a study-group, the ‘Bouwkundige Studiekring’ BSK (‘Architectural Study Circle’), aiming to discover themselves the very basics of architecture, which they missed in regular teaching. During a year Hans guided this group, assembling at professor Granpre Molie re’s house. The papers of Le Corbusier and those of ‘De Stijl’-group were discussed, as well as the just published book of Jacques Maritain: ‘Art et scholastique’. The last lecture given by Hans in the BSK was about the Domtoren in Utrecht and implied a serious trial to fully investigate the ins and outs of its measures.

Sacristan and designer

On 26 May 1929 Hans van der Laan and his fellow-novice Herman Diepen made their profession in the abbey. In 1930 the monks Van der Laan and Boer were set to work in the vestment-atelier, which was established above the sacristy and in 1931 Hans was appointed as second sacristan in the abbey under father Pieter van der Meer de Walcheren. On 2 September 1934 he received his priest-ordination together with his confrères Bertrand de Poulpiquet du Halgoët and Nico Boer. In 1936 father Hans was charged with the guidance in the sacristy, which he would retain till his departure to Vaals in 1968. Most of his time he spent on renewing the inventory of the church and sacristy in Saint-Paul’s abbey, though that was not all, according to some smaller building-assignments in the same period. Father Hans described the beginning of these activities as follows.

When in my noviciate I had to make the design of new choir-stalls in the abbey church I had recourse to the tower of Utrecht, which I brought along from the world as a final achievement. After a year they stood in the church and the chair of father abbot as well, all according to the same countable proportions, but the effect was very poor. My final drawing was the praying desk of the abbot, but meanwhile something had happened. The parish priest of a nearby village Baarle-Nassau was engaged on building a devotion-chapel upon the foundations of a demolished gothic church, at least upon those of the choir. A builder and some bricklayers spent their spare time on that object. They were about a meter and a half high, when they didn’t know what to do with the forefront, especially because the priest wanted a small belfry on top of it. He came to consult father Bellot, but his adviser had already departed for good to France; that’s why father abbot sent me to the parlour, for I should have to know it as well. So that was my first real building-assignment and it was not without passion that I threw myself on it. However, the novice-master allowed me only half an hour a day to work on it, between the morning conference and the midday-meal. During two or three weeks these were moments of intense effort. With the tower of Utrecht before my eyes and the golden section of father Bellot at the back of my mind, I searched for a stable starting-point of the design. The problem was concentrated on the conflict between the flatness of the façade and the voluminosity of the belfry, the third dimension of which, I don’t know how, put me on the scent how to correct the golden section. I only remember the moment, going to the refectory, on a few meters from the door, that I received a clear insight in what would later be named the ground-ratio, and thereafter, during dinner, the calculation of the measures of the system that resulted from it. They lied near to the countable proportions of the Utrecht tower. I will never forget the experience to have found the stable basis which I had searched for all my time in Delft. It closed that period for good and even the whole period of my youth. Such a same moment I had experienced when in February 1976 the last sentence was formulated of lesson XIV of ‘The architectonic space’, by which the whole theory was put into words. After 1929 followed a period in which I measured all that I set my eyes on, in order to verify that ground-ratio and to control it completely. But the first what I drew was the praying desk before the chair of father abbot in the choir and the impression was no longer poor.

In 1930 he received the assignment to enlarge the chapter-hall of the abbey. This contained the restriction to follow in his design the overall style of father Bellot and he stuck to it strictly.

In his new monastic life father Hans remained still in contact with some fellow-students from Delft. And the most direct contact was with his younger brother Nico, who also had begun to study architecture in Delft. The two brothers were to the same extent captivated by the origins of architecture and they gained in the thirties some starting-points, which they tried out, after Nico finished his studies, in designing a new guest-house for Saint Paul’s abbey. For the first time this plan showed evidently a divergence from the existing style. The proposal initially evoked quite some resistance from the abbot and monks, but by the assistance of professor Granpré Molière, who had become friends with the abbot, the building was yet realized and afterwards abbot Jean de Puniet was thus satisfied that he promised father Hans the building of the definite abbey church. At the same occasion he allowed him to work out his newly gained architectonic insights with a group of like-minded architects and former fellow-students, among whom also Sam van Embden. This resulted in an initiative for six or seven meetings in Leiden and Delft during the war, in which the first beginnings were set down of the complete plastic number system. The years 1941 and 1942 father Hans had experienced as a rupture in his lifetime.

In that period all persons had died, with whom he once had an intimate relation, his mother, his father, his sister Jo, with whom he had a special tie, and also his monastic teachers, father abbot Jean de Puniet and his brother Pierre, the former novice-master.

The first years after the war

After the war father van der Laan was invited by the bishop of Breda to take guidance of a working party, charged with the rebuilding of the destroyed churches in the diocese. From April 1946 to March 1947 about twenty meetings were held in the Begijnhof (Beguinage) of Breda. These meetings implied discussions on various building-plans, as well as all sorts of treatises about theoretical standpoints. Moreover, his brother Nico was charged by the archbishop of Utrecht with the guidance of the ‘Cursus Kerkelijke Architectuur’ (CKA), a course for ecclesiastical architecture, which had been established in the ‘Kruithuis’ in ‘s-Hertogenbosch. Besides the joint development of architectonic views with students in small groups, Nico also organised the so-called general lessons, in which all aspects related to ecclesiastical architecture and liturgy were exposed by experts, such as liturgical singing, gesture and vestment, iconography, sculpture etcetera.

The lectures by father Hans himself, about liturgical vestment gave cause for a French publication in ‘L ‘artisan liturgique’, edited by the monks of the Saint Andrew’s abbey in Brugge. It was the beginning of a sequence of thirteen papers (1948-1960), also supplying necessary drawings to accompany the making of liturgical vestment into the ultimate details. The atelier for ecclesiastical art in the abbey of Oosterhout had become leading and its influence was not limited to the Netherlands, but was growing to international fame, thanks to Dom Xavier Botte of the Brugge abbey. In this way it could happen that Cardinal Lercaro, archbishop of Bologna wore mitres after the Oosterhout model, made in Assisi.

In 1948 the brothers Hans en Nico designed the Saint Joseph chapel on the outer border of Helmond. This chapel testified for the first time of the road the Cursus Kerkelijke Architectuur had turned into, namely the processing of the plastic number into the stylistic means of the first ages of Christianity, totally in accordance with the reform movement of Solesmes, just like the book ‘Le nombre musical grégorien’ by Dom André Mocquereau (1849-1930) had pointed the way for the reintroduction of Gregorian singing in church. The model of the Saint Joseph chapel was one of the first achievements of the CKA and the accessory analysis with the plastic number represented an important subject of research for many students in those post-war years.

In the year 1949 Dom Maximiliaan Mähler, the new abbot of Saint-Pauls abbey assigned to father Van der Laan, in co-operation with his brother, who meanwhile had established his office in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, the design of the necessary extension of the abbey, including the building of a new church. But the first sketches raised at once a considerable resistance in the monks’ community. Dom Mähler explained this as follows.

‘The presented plan by father van der Laan for the new church would have to join to the existing sanctuary by Dom Bellot. In the opinion of many of the monks the contrast between the two styles would not lead to a satisfactory solution. Therefore, after mature deliberation it must be decided to look out for other possibilities.’

Eventually it appeared impossible to reconciliate the risen opposite standpoints about the plan of father Van der Laan and one decided to give it up. Finally in 1956 a new church has been built after a design of architect J.H.Sluymer (1894-1979) from Enschede, with the co-operation of father J. Rahder. As a consequence of the passed discussion the church was located separately from the existing abbey-building.

Meanwhile the fifteen lessons about the ‘architectonic ordinance’ (1953-1956) in the Kruithuis were finished and in 1960 published in French by the editor E.J.Brill in Leiden under the title ‘Le nombre plastique’. This implied a direct reference to ‘Le nombre musical grégorien’ by Dom Mocquereau, the monk of Solesmes. About this intellectual source architect Sam van Embden, friend and fellow-student of father Hans commented in an article in 1991 as follows.

‘What firstly comes to my mind from our earliest conversations are the explanations about rhythm from ‘Le nombre musical’. In the introduction of his book Dom Mocquereau himself stated:

‘Il n’existe qu’une seule rythmique générale, dont les lois fondamentales, établies sur la nature humaine, se retrouvent nécessairement dans toutes les créations artistiques, musicales et littéraires, de tous peuples, dans tous les temps. (‘There exists only one general rhythm, whose fundamental laws, which are anchored in human nature, are necessarily found in all artistic, musical and literary creations of all people, in all times.’)

This shows the extreme influence of the reform-movement of Solesmes, coming to expression in the Benedictine tradition in Oosterhout, on the developing ideas of father Hans. In building-practice the office of Nico with his partners Wim Hansen and Harry van Hal played a primary role in promoting the joint goods of thought. The most important churches, realized in that period are: the Sint-Catharina church in Heusden (1950), the Sint-Martinus church in Gennep (1953), the Johannes

Geboorte church in Nieuwkuyk (1955), the Heilige Geest church in Vlaardingen (1959) and the Paulus church in Dongen (1965). The influence of father Hans was considerable in that period. Many architects asked him for advice, not only because of his ecclesiastical and liturgical survey, but especially on behalf of his architectonic insights, concerning profane buildings as well. Yet his influence and above all the realized churches gave rise to much criticism. His activities in Oosterhout and the churches of his brother Nico carried still too much the keynote of Solesmes and early-Christian architecture. The two brothers, fully convinced of their motives, were searching for the fundamentals of architecture, following the footsteps of Vitruvius. Because the concept of the basilical prototype represented pre-eminently an ideal ordinance and disposition, such as, obviously in the beginning pursued by them, they were very strengthened by the nineteenth-century Benedictine reform movement as initiated by Dom Guéranger. But in the fifties the criticism against this essentially archaic way of thinking and building was growing strongly. On a study meeting of the Cursus in June 1955 it had become quite clear that a change of course was inevitable.

The crypt of Sint-Benedictusberg abbey

In 1951 the abbey of Sint-Benedictusberg in Vaals had been founded a second time by a group of monks of the Saint-Pauls abbey of Oosterhout and father Van der Laan was asked by them to design the still missing crypt and church. He himself described that event as follows.

‘It was Saturday 6 July 1956, at about nine-thirty in the evening, that Dom Truijen, prior of Sint-Benedictusberg abbey asked me to finish the buildings of their abbey.

Together with the entire community he had come to Oosterhout to attend the consecration of the new church. When in the afternoon all went home again, he stayed behind in Oosterhout helping me to clear the sacristy, for he had been my second sacristan before. We were seated on the steps of the church on that beautiful summer evening, resting a while of all the work, when he suddenly said to me: ‘You were not allowed to build the church here, you may do it with me.’ Obviously for that reason he had insisted to help me with the clearing.’

That church with its outbuildings must complete the existing abbey-building, which was brought about after the design of the German architects Dominicus Böhm and Martin Weber. In 1956 the new community of Sint-Benedictusberg was still in its first founding stage. It was started with great élan and received firm support of the local Limburg population. The community was housed in a building that was neglected and unfinished, but that lied indeed in a beautiful landscape, and was amply designed. But the monks still missed the centre of their abbey, the church, the most needed building for a religious community. In their midst there were, beside prior Vincent Truijen (1916-2006), a fair number of monks advocating the ideas of father Van der Laan. Nevertheless, it was an act of utmost confidence to assign to him the realisation of the crypt and church. Here, fortunately were no signs of a bond with the work of Dom Bellot, such as in Oosterhout, neither were the new habitants of the abbey especially attached to the original building of Böhm and Weber. Many years thereafter, in 1965 father Van der Laan held a conference for the noviciate of the abbey, in which he reported the circumstances in 1956. He told that the invitation given then by prior Truijen meant, that the actual church above the crypt only would be built after fifteen years. By that fact he was obliged to make something, that must be accepted by people he did not know yet. Till then, as a starting point for him always served certain concrete forms, typical forms, which were based on a special, restricted significance. That way he had designed vestment, furniture, vessels and buildings and it was surely with a certain hesitation that he had to release all those things, only relying upon pure universal forms. He continued as follows.

‘The design of this church became the signal for that, because compelled by necessity I must make things in complete ignorance of the future. You can see it for instance at the former furniture of the refectory and that of the crypt. Exactly the same proportions are applied, but the first time I stuck to existing tables, in this case to the guest-table, while the other time, in the crypt I started from boards and I grounded my reasonings on a universal starting point. And I did the same for the chalices, etcetera. Thus in 1956 it was time daring to venture the leap, after visiting Rome in 1955, after Jan de Jong had graduated, after completing my study of the plastic number in 1956.’

Altered insights

Between 1958 and 1960 father Hans, together with Nico could try out this working method at the renewal of the Trappist abbey in Zundert, where abbot Emmanuel Schuurmans shared his opinions and was willing to really practice them as well. The growing change of mentality in those days before the Second Vatican Council came in the Dutch monastic communities at the most to light in Zundert. Father Hans designed in the inner court of the Zundert abbey for the first time a gallery, the lintels of which were not resting on round columns with capitals, but directly on rectangular piers. After the construction of this gallery he visited the abbey together with Jan de Jong. Thanks to the positive reactions of his companion he felt strengthened in his choice also to apply such rectangular piers for the crypt of Sint-Benedictusberg abbey. The crypt in Vaals consists of an oblong space, which is divided by two pier-settlements and has on both along-sides a row of cellas, serving as chapels. The two transverse endings consist of closed, flat walls. The central positioned altar is consecrated to Saint Benedict. The side-chapels served at the time for the low masses, which till 1961 still were celebrated in the morning by all priests separately. The closing wall behind the high altar bears the names of those who, with their financial support had made possibly the construction of the church and who are buried behind that wall. On 1 March 1962 the consecration of the altar took place by bishop Petrus Moors. One day later father van der Laan held a lecture, about which father Nico Boer afterwards gave the following description.

‘In the evening he gave a masterly and for a child comprehensible conference about the style of our church, as a monk, as a sacristan and as an architect. Our life is simple, our singing is simple, especially the psalmody which, with her few intervals can be perfectly beautiful; our ceremonies are simple: entering in a double row holding procession, standing in two rows opposite to each other; our vestment is simple, such as we reduced our liturgical dress as well to its essential form. Things like that must be possibly with a church as well, simply by the harmonic position of properly proportioned, extremely simple parts, what the Ancients called symmetry and eurhythmy. The perspective drawing of the crypt showed something silly and trivial; the client as well as the architect put an act of confidence in the science of intervals and that was not falsified. The spatial result is clear, harmonic, beneficent and above all sacred and holy.’

All in all, his theory on architecture had also made notable progress by the Cursus and father Van der Laan had been able to realize a building without the influence of any existing stylistic feature. But he also was aware that his theory was not complete, because the influence of the ‘dispositio’, the design was still missing largely while in the crypt primarily the ‘ordinatio’, the determination of measures had played a central part. From 1960 to 1963 he gave in the Kruithuis a new series of fifteen lessons about architectonic disposition. This study would mark the beginning of his book ‘The architectonic space’, which would be edited only in 1977. When the crypt was built he continued by designing furniture, consequently following the same basic standpoints as in building. After his own words:

‘By its articulations furniture is able to continue the joint proportions of the house. In that way it can complete the domestic symphony of spaces and forms into the full answer we owe as humans to the great harmony of nature that surrounds us. If furniture is designed in this way and it harmonizes with the spaces it is standing within, further decoration is superfluous. It is by itself the very ornament of the room, in which is then good to be.’

The crypt was the first building, in which architecture and furnishing formed such a unity. In 1973 the design of a complete series of furniture was completed. In Sint-Benedictusberg abbey all dwelling spaces, including those of the existing building were supplied with such furniture, by which a great unity was achieved in the whole house.

The abbey-church of Vaals

At the end of 1964 Dom Nicolaas de Wolf (1931-2015), monk of Saint Paul’s abbey was elected as abbot of Sint-Benedictusberg. In 1966, finishing the first building stage, the cross-monument was erected on the square before the crypt, a pillar of freestone with a cross on top of it. In the initial plan for the new church this cross was not provided. It was a concession to an objection made by the ‘Limburgs Welstandstoezicht’ against the high, mainly blank façade of the church. The cross must serve as a visible sign for the church standing behind it. At the blessing-ceremony father Hans said to the ‘Friends of the abbey’ about it:

‘When you arrive at the abbey, you ride between the trees to the ample front square. Aside there are the edges of the woods and before you the long side-façade of the church. By the advanced position of the porter’s lodge on one side and by the oblique-standing wall on the other side, but especially by the cross, standing in the middle of the façade, the head-ending of the front square becomes a sort of a gallery, connecting the framework formed by the edges of the woods.’

On 4 may 1968 the consecration of the abbey-church took place by bishop Moors.

Father Van der Laan gave the following account concerning the basic concept of his design :

‘Father Bellot built the churches of Oosterhout and Quarr as a sequence of three spaces: one space for the faithful, one for the choir of monks and one for the ceremonies around the altar. That last part, to which the other two were pointed at, was called sanctuary; it surpassed the two others in height, light and decoration. Consequently, his churches were long and narrow. When I entered the cloister, I soon resisted against such a disposition, by which liturgy became a show more than a joint event. In my opinion the altar must take its position in the monk’s choir, between the choir-stalls. Especially when I became sacristan one day, I dreamed of a disposition like that, such as now is confirmed by Vaticanum II. Both designs which I made after the war for the church of Oosterhout were rejected, above all things for that reason. Next to this, the argument was put forward, that such a wide choir was unfit for a good antiphon singing between the monks. The church which is consecrated in Oosterhout in 1956 therefore maintain still the formula of Dom Bellot. For me the space of the choir with the altar had to be about square, with a narrow strip behind it for the ceremonies, because they should be celebrated facing the people. And the part for the faithful also had to be not longer than wide, because in a longer space the involvement of the people in the celebration of the liturgy should not come to full advantage. So I must come to a total space with a surface of 3 : 7, but I did not come further than the derived form, namely 2 : 16/3 or 3 : 8, by which the church counts three bays wide and eight bays long, with a window-settlement of fourteen windows in length and five windows in width. As such an oblong hall the church of Vaals is designed, preceded by an atrium, companied by two galleries and finished by a transverse gallery. The atrium itself is surrounded again on four sides by galleries. Above the pier-settlements of the three galleries and the blank end-wall of the hall, windows are placed around, also in the form of pier-settlements, which support the flat ceiling. The galleries of the hall, such as those of the atrium are covered with flat roofs, the hall itself by a saddle-roof with tiles. Fitting the church in the total arrangement of the existing abbey of Böhm and Weber, an atrium was needed, but I gratefully accepted that necessity, because it gave me the opportunity to transform the galleries and atrium into a great dense substructure, above which, by the open lantern of windows and roof the very hall-space manifests itself. But for another reason again I was inclined to insert the atrium in the total concept of the church. I was just fascinated by the resemblance between the liturgical arrangement in the church-space and the whole of the composing parts. On the one hand there are the atrium, the two side-galleries and the transverse-gallery, which together enclose the church-hall and on the other hand in the church itself the part for the faithful, the choir-stalls on both sides and the space behind the choir enclosing together again the more intimate space in which the altar is placed. And then I had still a final disposition in view, that of the altar itself, which I saw as a planum, a platform of one step high, a new marking out with the altar upon it, formed as a core-block. Here we would find again for a last time the same disposition, but now in the reverse direction. This became the keystone of the whole composition.’

On 18 October 1968 father Van der Laan changed his domicile from Oosterhout to Vaals, where in 1970 he became official member of the community of Sint-Benedictusberg. This community kept belonging to the Congregation of Solesmes and did not enter the Dutch Congregation of Benedictines, which was founded in 1969. In his new home he also was appointed as sacristan, so that he could continue his familiar daily work and in 1973 he was elected as a member of the Council, the board under the guidance of the abbot.

A wider interest

After the consecration of the abbey-church he restarted his lessons in the Kruithuis with a final series about architectonic space, in which he also implicated the disposition of the town. A journey to Southern Italy in 1969 and especially his acquaintance with the temples of Paestum and the Roman houses in Ostia meant a solid affirmation of both the results of his study and his practical experience at the abbey-church in Vaals. Beside it a reportage of the megalithic monument Stonehenge was of great influence on these final lessons and consolidated for him the fundamental significance of the insights he had acquired in all those years. An analysis of this monument and a scale-model with its composing parts, made in freestone formed the keystone and foundation of his entire theory.

The lessons in the CKA were ended in 1973, whereafter he had described the theory systematically and finally in 1977 it was edited, again by E.J.Brill in Leiden under the title ‘De architectonische ruimte’ (the architectonic space). A praising and enthusiastic article about the striking newly built abbey-church in the Belgian paper ‘De Standaard’ by the editor Anthony Mertens, resulted in a visit to Vaals by the Marian Sisters of Saint Francis from Waasmunster. Out of that contact spontaneously followed the assignment to father Hans for a new convent for twelve sisters and twenty-five guests on a beautiful sloping site, surrounded by woods on the edge of Waasmunster. This assignment for ‘Roosenberg Abbey’ came for father Hans on an ideal moment in his life, when he just had finished both his complete study and his magnum opus. The construction of it was

accomplished in a short time in the years 1974 and 1975, by collaboration with the office of his brother Nico and the architects Piet and Edmond De Vloed in Melle. The realized building still makes an indelible impression by the directness of its appearance and the obvious absence of any compromise. A few years later he was asked again to renovate the existing mother-house of the same congregation in the Kerkstraat, in the middle of Waasmunster and to make it suitable to the more contemplative life that the sisters wanted. The result was a totally new arrangement of buildings around three courts, only preserving the existing neo-baroque church within its newly attuned situation.

In the autumn of 1978 father Hans was asked by architect and teacher Jos Naalden, whom he had already met in Oosterhout, to design a new dwelling-house for him in Best, on a lot with a double house destination. This request leaded to a prototypical concept of a classical court-house, in full accordance with the described spatial patterns of ‘the disposition of the town’, in chapter XIII of his just published book In 1982 the house was completed and supplied with the same furniture he already designed for Vaals and Waasmunster.

General publicity

In 1979 Jos Naalden and William Graatsma, both engaged at the faculty of architecture of the Technical University Eindhoven and J. Szénassy, managing director of the Bonnefanten-museum in Maastricht asked father Hans to make a visual performance of the theory of ‘De architectonische ruimte’ for a greater public by means of models and short explanations. The 45 models and 12 pieces of furniture which he developed for this purpose were exposed under the title ‘Architecture, modellen and meubels’, with an ample catalogue and started from 1982 in Maastricht, Eindhoven, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, Nijmegen en Gent.

At the exposition in Eindhoven also appeared a publication ‘Letters in steen gehouwen’ (Letters carved in stone) with instructions for an alphabet of classic carved letters, which stood model since a long time for the many inscriptions in Vaals, Waasmunster and the churches of the Bossche School.

Meanwhile father Van der Laan was still working on the monastic framework of Sint-Benedictusberg abbey which acquired in that way step by step its full coherence. Because in 1965 the exploitation of the gravel-quarry behind the abbey came to an end, it became possible to lay out an appropriate cloister-garden. The design for it was accomplished in co-operation with the landscape-architects Pieter Buijs and Bob van der Vliet in ‘s-Hertogenbosch. Thereby the abbey-complex had gained its own convenient environment amidst the surrounding Limburg landscape. In 1980 the existing inner-court of Böhm and Weber was renovated and rearranged, by which the whole abbey, including the already realized building-phases of 1956 and 1968 presented a pure and persuasive total unity. Father Hans himself said about this phase:

‘Now that we have removed in the house all the leaded lights, which hindered the sight of the inner-court, the house has become more picturesque, for that court has a rather romantic architecture. As a minor counterbalance I built the small gallery in it, reminding of the severity of the church, and now the court shows its contrast with the blank church to its full advantage.’

In 1985 the master-plan of 1956 could be finally completed with the enclosure of the second cloister-court, by building the library-wing and the open gallery to the garden. About this final building-phase father Hans said in 1987:

‘But now I would insert the whole world of my architecture in a deeper perspective. I always founded my studies on the observation of nature, in a very primitive way. They concern the origin of inner spaces amidst the space of nature, raising freely above the earth-massive, and now we take away something out of that massive – one may say to form bricks for walls – and with that, take off pieces of inner spaces from the space of nature. In that way we started our theory. But especially after the exposition of 1982 I noticed that something had been left to study. After I had developed that primitive starting point to the theory of the plastic number, the architectural counterpart of the ‘nombre musical’ of Dom Mocquereau, I could develop from there the whole lay-out of the house and even of the town, just as Dom Mocquereau could inspire with his ‘rythme élémentaire’ and his ‘grand rythme’ the entire Gregorian repertory.’ But it has become evident now, that when the house is ready, after it has been taken away from natural space, it must be given back as an external building to the same natural space. Though I have done it always instinctively somehow with our church and the cloisters in Belgium, I did never know the rules of it. The pervasion in this phenomenon has only begun in 1983, when I had to design the last extension in Vaals. In the new library-wing, in relation to the church one may see something I was specially aiming at: the arrangement of buildings in various directions in nature. Just as I made sticks for the proportions of measures and wooden blocks for the various forms, so again, I made a series of freestone forms to research and illustrate those compositions of buildings ‘

In the same year 1985 ‘Het vormenspel der liturgie’ (‘The play of forms – nature, culture and liturgy’) was published, in which he justified his ideas as a monk and as an architect and summarized the great liturgical framework in which all his work had been contained. That book was not only a compilation of his own opinions, but it meant also an act of support to the Benedictine reform movement of Solesmes, by which he was deeply influenced during all his life and work.

In March 1986 the Benedictine sisters of Tomelilla in Southern Sweden asked him to design also for them a new cloister. Father Hans still had been capable to finish the whole design of that cloister, but the plan had been finally edited by his nephew Rik van der Laan, in co-operation with Rudi de Bruin, a Dutch architect working in Sweden. In 1995 the first part, consisting of the great court and the church was realized. But the sisters finally relinquished the entire project, which still contained a second court for guests. For father Hans this cloister Mariavall, as he characterized it by himself was the last specimen of his life-work and his most complete design.

On 20 September 1986 his brother Nico died, who always had been a true companion for him and now had found his last resting-place in the crypt of the abbey-church in Vaals. In 1989 the realization of the second cloister-court formed the occasion for the Ailbertus foundation to award father Van der Laan their triennial price of architecture for that final stage of his work. At the same opportunity his last insights in architecture, titled as: ‘An architecture based on the spatial qualities of nature’ were also edited by the same foundation. In 1993 the English version of it was inserted in the encyclopaedia ‘Companion to Contemporary Architectural Thought’, under the title ‘Instruments of order’.

On 19 August 1991 he died in his own abbey, where he was buried on the graveyard in the garden. William Graatsma wrote later about him: